Repetition in “A Tragedy” mostly contributes to the overall substance of the work. It is the repetition of onomatopoeic words like “flop” and “plop” that further torment the speaker of the poem and bring him ever closer to his (soon to be) eternal underwater prison, while it merely reminds the reader over and over at how ridiculous the melodrama is.

Nonetheless, there is a more complex use of repetition in lines 42-46. Line 42 contains the phrase “I can dare” and in line 46 it is said twice as an exclamation. It is interrupted by a parenthetical, the only one of the poem, and it is a variant on lines 2-4 and lines 23-24. Here the double-level repetition is quite fascinating to consider. The first level is of the phrase “I can dare!” Line 42 is a statement referring to the latent courage it takes in order to make the choice to commit suicide, even in such a time of emptiness. The parenthetical seems to be showing that these onomatopoeic sounds (the second level of repetition) are now completely immanent within the speaker. They have consumed his thoughts, his heart, his very soul which before (lines 18-20) were at least still capable of shrieking, and therefore still expressing an internal human reaction. He has become the water into which he is about to drown himself (more on this idea under “Despair”). The idea of repetition as active extension plays into these lines as well. Under this idea, repetition can be thought of as a miracle; one element all of a sudden, through some anomalous action, replicating into an infinite series. The exclamation points in line 46 seem to affirm this spirit of repetition. It has always needed to repeat, and now that it has, it wants to show the entire world. One can also interpret the parenthetical recapitulation as the cause or motivator behind his decision to drown himself.

The reason these few lines could come across a bit contrived to the reader is because the form of the poem becomes incredibly apparent. Do we really need to be reminded again (almost verbatim) that the barges make “plopping” noises? It results in a pseudo-symmetry of form: the gross sounds are the first things we hear and, of course, they are the last the speaker hears as he submerges himself into death.

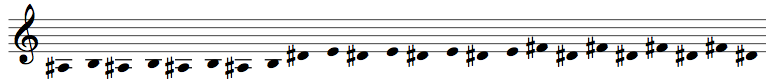

Along with a few specific musical objects that recur throughout the album (Shaggs Example 1 in various forms is sung on the songs “Philosophy of the World,” “It's Halloween,” “Why Do I Feel?” and very prominently on “What Should I Do?”; antiphony featuring on “That Little Sports Car,” “Who Are Parents?”, “My Pal Foot Foot” and “Sweet Thing.” As with the cadential melodic phrase, the antiphony seems to culminate in the last track that it appears on in the album (see “Surprise” for more on the antiphony in “Sweet Thing”)), The Shaggs maintain a consistent sound world (described in “Surprise”) that all sounds very repetitive.

Shaggs Example 1:

In addition to the examples listed before, there are a couple of isolated passages on the album that tend to use repetition more as a trajectory than just strict repetition:

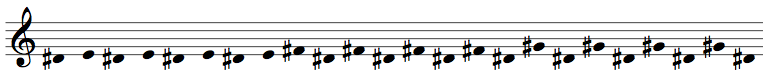

-At the end of “Who Are Parents?”, the chorus is repeated three times (Shaggs Example 2). In the third time, the chorus is sung more delicately and the instruments all play a bit softer, simulating what appears to be a fade out (and perhaps going along with the image of a parent tucking in their child at night as they are falling asleep). What is baffling is that in the second iteration The Shaggs repeat the chorus at exactly the same volume and in exactly the same way, denying the trajectory from loud to soft that definitely is hinted at because of the third iteration.

Shaggs Example 2:

-The chorus of “Things I Wonder” opens the song, and is recapitulated near the end of the song (Shaggs Example 3 at 1:20). The only differences in the repetition are in what the drums are playing and in the lyrics of the third and fourth lines (and a bit melodically). The first time the drums play a standard and simple rock beat that tends to lag behind the melody. When this passage comes back near the end of the song, the first two lines of the lyrics are the same: “There are many things I wonder/There are many things I don't,” but now the third and fourth lines are sung: “I'll be glad when I find all these things out/But until I do things won't change with me and you.” Yet they have changed; the drums are now playing an odd slow(ish) drum roll on the snare drum and a hi-hat opens and closes to mark the beat (which also lags). Can it perhaps be a sub-conscious optimism of The Shaggs that things ultimately do change?

Shaggs Example 3:

Repetition abounds in The Room. It is everywhere and on all levels. Aside from recurring lines and actions that certain characters seem to say abundantly (Claudette: always affectionately touches Lisa's nose before exiting a scene; Michelle: “You guys are too much!”; Denny: “I have to go.” Mark: “Johnny is my best friend.” Johnny: “Oh hi Denny/Mark/babe!”, “That's the idea!”), there is the insane amount of establishing shots that feature different famous landmarks all over San Francisco. Then there are scenes in which it seems like a character has forgotten their line, so just repeats what he or another character has said previously (You didn't get it,did you?... I'm very busy...how much did you pay for the dress?...chocolate is a symbol of love..., bringing up the psychologist thing...). There is literal repetition (recycling the same footage in a new sex scene) and weird repetition (pouring alcohol into alcohol). The lasting effect on the viewer is more of a wtf?-kind of effect, where it seems that redundancy is championed above all things. Extreme focus on the repetition of the mundane and impertinent is the name of the game in the following two scenes:

- In The Room Example 1, Johnny listens to Mike's dilemma (or, “tragedy” as he eloquently puts it). About fifteen minutes earlier, we see the story Mike is referencing. Mike and Michelle get caught having sex in Johnny's apartment by Lisa and Claudette. As they leave, Mike suddenly remembers he forgot his underwear. So, he quickly re-enters the room trying to inconspicuously steal them back, but fails as Claudette sees them, snatches them and holds them up in front of Lisa and Mike (or “everybody,” as he so eloquently recounts).

The Room Example 1:

James MacDowell's critical analysis of this scene (link) points out the incredulity the viewer starts to experience as this two minute scene solely revolves around a drawn out re-telling of an insignificant detail that already happened: “this scene takes redundancy to the next level by existing solely in order that we may be retold of something which we have already witnessed: Mike’s “underwear issue”. To pile inconsequence upon yet further inconsequence, the original event to which the anecdote refers was itself wholly surplus to narrative requirement, a moment of ‘comic relief’ whose relevance we have already likely had cause to wonder at.”

The end of this scene has Mark enter only to implore Mike about his underwear story. Still! Then all of a sudden the mood changes and goes from unbelievable to unbelievably unbelievable when Mark accidentally pushes Mike into the trash cans and he is asked if he needs to see a doctor (more on this in “Outer Voice”). In this case the redundancy seems to allow things to spin out of control, or to further push the affect into a less believable scenario. The Room is not without a large share of building small climaxes only to never mention these sub-plots again (i.e. Claudette's breast cancer, Denny's experience with the drug dealer, etc.).

- Another scene in which redundancy is all too pervasive is the coffee shop scene, shown in The Room Example 2:

The Room Example 2:

The scene is preceded by an establishing shot, and then what appears to be another establishing shot, and Johnny walks through the frame (bizarre redundancy). Before he is off camera, the viewer starts to hear the sounds of a coffee shop. The camera cuts to a close up of a latte being made. Then there is the following dialogue:

Female barista(off-camera): Whipped

cream? Sure.

Female customer #1 (off-camera): I'm

gonna get a slice of cheesecake and a bottle of water.

Female customer #2: Umm, I'll have a

large peanut butter cup with extra whipped cream please.

Male barista: All right.

Male customer #1: And I'll take some,

uh, cheesecake and a coffee.

Male barista: OK, why don't you guys

have a seat? We'll have that right out for you.

Male customer #1: Good.

Female Customer #2: Thank you.

Female barista: Hi! How ya doin'?

Female customer #3: Hi.

Male barista: How's it goin'?

Female barista: What would you like?

Male customer #2: Can I get a bagel and

Americana?

Female barista: Whipped cream? Sure.

Female customer #1: I'm gonna get a

slice of cheesecake and a bottle of water.

Male barista: Yeah sounds good why

don't you guys have a seat we'll have it right out for you.

Female customer #1: Thank you.

Johnny: Oh hi Susan!

Anyways, then Johnny and Mark proceed to order as well. That's seven and a half orders (the half being the end of the first order the viewer hears before anyone is on camera). However, notice that the first two lines of the printed dialogue are repeated exactly (except with the people on camera this time) later on. What is going on here? First, it is absolutely absurd to establish that, yes, we are now in a coffee shop where people order cafe-like food and different types of coffee almost 6 times before the main characters walk in and place their order. Second, why are there two baristas taking orders from the same customers? Surely it's not slow in there, after all, look at all these customers. Third, it is absolutely hysterical that the sound chosen at the beginning of the coffee shop scene is the same exact sound that is then repeated when the characters are on the screen.

As in the recounting of the underwear story scene, the redundancy here also allows things to spin out of control, but in a slightly different way. The dialog of Mark and Johnny that follows at times is also incredulous, and seemingly non-sequitur. The female barista brings their coffee only to further ask if they want any cheesecake. They say no but she says “It's real good...” Denied a second time she takes off. Then Johnny answers Mark and tells him that the bank Johnny works at just got a new client. Mark wants to know who it is but Johnny tells him it's confidential. And then: “Anyways, how's your sex life?” This utter turn in conversation is mind-numbingly staggering, speaking of non-sequiturs, etc. Here, there is also repetition as Mark returns the gesture and tells Johnny that he cannot talk about it. Immediately after that Johnny says he has to go. The entire conversation barely hangs together as a natural conversation that two friends would have.

The level of torment the speaker tries to convey is extreme in itself throughout the poem. However, when it is revealed that this torment is possibly because his friend stole his love, the reaction turns to complete disgust. In lines 31-38, the speaker focuses on his lover's affair with his “Friend,” although he lays a curse on his friend (line 31), the surprising part comes in lines 32, 37 and 38. Here we have a new term, “Ugh!” Now, this in itself might not be the most shocking thing, as for most of the poem, Theo Marzials has insisted on creating an onomatopoeic world with some phonetic consistency, and “Ugh!” is a guttural expression, just as perhaps “Plop” and “Flop” are also nature's guttural expressions. Yet, I can't help but think of a melodramatic female high school teen suddenly grossed out by one of her less mature male peers and then expressing the same exact sentiment: “Ugh!” It isn't until lines 37 and 38 when the reader truly can potentially become bewildered at Marzial's decision to repeat “Ugh!” not just once, but twice.

However, what's interesting here is that the disgust which the speaker is expressing is not directed towards his friend and lover, it is in fact directed at himself. In line 32, “Ugh!” is followed by “yet I knew – I knew” and again in line 37. A lot can be read into this. For instance, if the speaker knew about this affair, why did he not confront them before it was too late? Also, this self-disgust seemingly sheds more light on his psychological state at the point of suicide. The disgust, although an inward one, is reflected on the outside with the gross images painted of his natural surroundings: “slimy branches” (line 6), “thin grey sky” (line 7) and “oozy waters” (line 9) are a few examples.

It is also worth considering the gestural component of “Ugh!” as a connection to revulsion, or perhaps even expulsion, as in vomiting. Before the speaker seems alarmed about everything leaving his body (“My love is running out of my heart” (Line 19) ), yet with “Ugh!” it's as if there is a new acceptance of inevitable death, and that the speaker might actually be trying to forcibly expel the remaining humanity he still has within himself; after all, he knew all along.

Listening through Philosophy of the World, it becomes apparent rather quickly that, true to the album title, there is one general pervading philosophy (that the pinning of hope against despair always results in mystery, and that it is best to leave that mystery alone), and the musical texture is one of the more salient features on the album to help support that notion, and to create a distinct sound world.

The musical textures change at times, but mostly stick to the following behavior:

-Windy, aimless and conjunct melodies (except at some cadences) mostly sung by two voices in unison (except at times when the second voice antiphonally repeats the last word of a line). The pitches sung are normally adjusted to the tuning of the guitar, with some exceptions. The melodies do not conform to traditional 4-bar regularity, with symmetrical phrases forming an antecedent/consequent relationship. They are instead sung almost as if without regular meter and form mostly asymmetrical melodic phrasing.

-Homophonic (rhythmically speaking) doubling of all vocal rhythms by electric guitar, either playing just the pitches being sung, but more often than not playing chords which begin to approximate traditional tertian or modal harmonies utilized by early rock music. However the guitar sounds “out of tune.”

-Drums that modulate tempo constantly but slowly enough to recognize it as some pulse that is present. Occasionally the voices and instruments lock in with the beat being provided by the drums, however it is transient. The drum material oscillates between primitive repetitious patterns, and extended drum rolls that act as fills or solos.

-The

tuning of the guitar in “My Companion.” Until this point in the

album, the guitar has always sounded out of tune (to standard guitar

tuning), but something that needed adjusting as opposed to this track

which sounds like it needs a complete overhaul (Shaggs Example 4). “My Pal Foot Foot” shows signs of degradation compared to the

first three tracks, but not to the level reached in “My Companion.” Thus, in a weird way one is almost set up to expect the continuing

out-of-tuneness as the album progresses, but the rate is alarming. I

imagine they recorded the first five tracks without re-tuning their

instruments. After “My Companion,” the sixth song on the album

“I'm So Happy When You're Near” returns to their favored not so

extreme out of tune harmonies.

Shaggs

Example 4:

-The vocal antiphony on “Sweet

Thing” (Shaggs Example 5). The antiphony on this album is mostly

reserved for Betty repeating the last word or couple words of a line

that Dot has just sung. However, the antiphonal role is expanded a

bit in “Sweet Thing.” This is the first time on the album in which

the vocal echo is repeated itself. Dot starts off: “You're such a

sweet thing” and Betty replies “Sweet thing, sweet thing.” This changes the conception of the antiphony because by repeating

that phrase twice, the response has not only become as long

(durationally) as the call, but has forced the listener to consider that this boy really is very sweet. As the lyrics progress, the antiphonal response takes

on a bit of a nostalgic quality. The listener soon finds out that

the boy has a mean side and has hurt the singer by cheating on her. There is an interesting progression in how the antiphony is treated

in this song. The first phrase to be echoed is “sweet thing.” After the second and third stanzas are sung by both singers in

unison, the antiphony returns (featuring in one line in each of the

next three stanzas, always repeating the phrase twice) on the

phrases: “fool me,” “coming” and “hurt you.” The end of

“You think you'll fool me” is repeated, almost like a challenge. Then the ends of the lines “But your turn's coming” and

“There'll be some girl who will hurt you” are repeated, and they

take on a more spiteful tone, as if she knows fully well that this

is a just world, and this boy will get what he deserves. Shaggs

Example 5:

The following stanza is the only time

on the album in which Betty repeats the entire line that Dot sings

before Dot has finished singing the line (Shaggs Example 6). A true

echo Though these lines comes across as a short failed round, they can be interpreted as the girl in the song is in some way splitting from her

tormented sub-conscious. This is done twice in the stanza on the

lines “In the end you will find” and “In the end you will see,”

signifying a level of acceptance, and an acceptance of a loss of

control. In the end, she can't do anything about it, but nonetheless

clings to her idea of a just world. The splitting of the voice like

that dramatically allows the antiphony to return to repeating the

original phrase “sweet thing” in the end, and recapture the

original nostalgic effect it had in the beginning of the song. Shaggs Example 6:

The movie constantly is trying to hammer home a ground of daily life to offset the more extreme developments of the plot. Scenes featuring football throwing, visits from Lisa's mom, running in the park or chatting in a coffee shop try to establish a normalcy. In all of these examples there are odd quirks that fail to capture the nature of daily life. For instance, almost all of the football throwing is over incredibly short distances, the dialogue is stilted and its almost inhuman deliveries bring to attention the incredible non-naturalness of all these activities. It is as if they are trying too hard to establish the beauty of the mundane, and as a result, create an odd and amazing artifice. Because even though the failure here is apparent, there is still an unbelievable success in creating an eccentric flow to the film. The film still succeeds in creating a ground, it just happens to be an odd ground.

I would like to focus on one sequence that has the power to absolutely stun the viewer (The Room Example 3). I am talking about the flower shop scene in which Johnny stops into the shop and purchases a dozen red roses for Lisa. The movie utilizes a common film technique known as ADR (automated dialogue replacement) in order to ideally have a cleaner and more intelligible dialogue track. However, in The Room, often this method becomes a distraction (if the re-recorded dialogue does not exactly sync up, if there is ambient noise in the dubbed track that conflicts with the ambience one would expect from the scene, or if the sound level is not present enough or too present in the overall mix) to the plot, and makes the world that Tommy Wiseau is creating that much harder to believe. However, in this particular scene, new extremes are reached with the timing of the dialogue, the mix of the music to the dialogue, and the very dialogue itself.

The Room Example 3:

About half the lines spoken in this scene come when the viewer cannot see the actor's face (this is mostly at the beginning and the end). The dialogue is transcribed here with each line marked if it is spoken visibly.

Johnny:

Hi. (not visible)

Flower Shop Attendant: Can I help you? (not visible)

J: Yeah can I have a dozen red roses please?

FSA: Oh hi Johnny I didn't know it was you…

FSA: Here you go (not visible)

J: That's me!…How much is it?

FSA: That'll be 18–

J: Here you go–

FSA: –dollars.

J: –keep the change. Hi doggy!

FSA: You're my favorite customer. (not visible)

J: Thanks a lot, bye! (not visible)

FSA: Bye bye! (not visible)

ADR provides a chance for a scene to have a more natural sounding delivery of dialogue. Considering more than half the lines were spoken when the actors' mouths were not visible, Wiseau could've taken some liberties in trying to salvage any notion of normalcy in this scene. Instead, this might be one of the most awkward dialogues in the film.

The absence of a visible locus to some of these lines creates a disembodiment and makes some of the lines feel less like story development, and more like objects floating around in a flower shop. What also reinforces this idea is that the lines are delivered in an almost non-sensical way. The timing from the flower shop attendant's “Oh hi Johnny...” through “You're my favorite customer” is rather odd. First, it seems implausible that she wouldn't recognize Johnny simply because (presumably) he was wearing sun glasses, especially since she is on a first name basis with him. His response to “I didn't know it was you” should've come before she said “Here you go,” but it's as if he forgot his line, and decided to deliver it anyway, “That's me!” Then he asks how much the cost will be, and she almost immediately responds “Eighteen dollars.” Yet, what betrays the believability of all this redundant and frivolous dialogue is the fact that Johnny responds with “Here you go” before she is even done telling him how much the flowers cost, and he hands her the money that all of a sudden he is holding (where in the shot before he is not holding any money). Of course he knows how much they cost because it's clear that he has been in there before on many occasions buying roses for Lisa because he's such an outstanding guy. In fact, Johnny is the flower shop attendant's “favorite customer.” What is remarkable here is that the repetition of “here you go” points out its oppositional use (timing-wise) in this scene. The first time it comes hesitantly with space preceding it, supposedly which should've been filled with “That's me!” The second time it is rushed and it cannot wait to be uttered, so much so that it creates a disordering in the dialogue again, however, this time coming too early. The repetition of this line also contributes to the feeling that these lines are bouncing back and forth with no meaning through the air as independent objects.

The scene is not completely redundant however, it accomplishes in establishing that Johnny is an upstanding guy by his actions: supporting a local business, buying flowers for his “future wife” Lisa, showing gentleness towards the little dog on the counter, and showing generosity by allowing the flower shop attendant to keep the change.

It is hard to rip away from the drenching quality that this poem creates through the “Me! Me! Me!” kind of tone. Most of the time the speaker is wrapped up with only his own thoughts. Of course, this makes some sense, as he is ending his own life. There is another voice, though, that is not the speaker's. This voice is the collection of onomatopoeic sounds that are peppered throughout to create an odd phonetic blanket throughout the poem.

The outside voice here is nature. It is the body of water in which the speaker is drowning himself. Barges normally are used in canals or rivers, but, the words “flop,” “plop,” “drip” and “drop” do not suggest a river or stream; they suggest a static swamp with a thick viscous algae surface bubbling up, oozing and slowly consuming the speaker. Nature's voice is used not just to establish a certain kind of phonetic sound for the poem, but to act as the ultimate end into which the speaker decides to drown. In that sense, it is only logical that these water sounds would create a consistency that consumes all other sounds, because the onomatopoeia is not just actually sounding from the water. In fact, most of these words are iterated even more from the speaker, describing his surroundings with sound. His descriptions become completely entangled with nature, as in lines 7-8 when he talks about the “slimy branches” pinned against a night sky: “As they scraggle black on the thin grey sky,/Where the black cloud rack-hackles drizzle and fly.” Not only is there internal repetition with “black” and “rack-hackle,” but there is an insistence on the vowel sound in “black” before releasing twice to the liquid vowel sound in “sky/fly.” It is also aggressive in repeating “k” sounds seven separate times.

A potential cognitive dissonance in this poem stems from these nature sounds. It is unfortunate for Marzials that the words “flop” and “plop” are associated with the pathetic, and with the humorous. Picture a goofy hound puppy running towards you, tripping over his floppy ears. Plop. Given different onomatopoeic sounds, some of this poem might have maintained a bit of serious drama within the melodrama.

The last song of the album “We Have a Savior” is preceded by a singular moment. Bob Olive, the recording engineer, can be heard saying “Take two” (Shaggs Example 7). There is a quality to his voice that borders the line between fatigue and exasperation, it almost sounds like this could have been the last song during a long recording session.

Shaggs Example 7:

I wonder what “take one” sounded like. The apparent second attempt at “We Have a Savior” produces bizarre results. The first sounds are a short guitar intro that is doubled rhythmically by the drums. However, they are rhythmically together throughout the intro! A ray of light and all of a sudden there is synchronicity! We do have a savior! Yet, as soon as the vocals start, the drums immediately fall out of sync again, following the dominant trend on the album. There are a couple of aspects though that are a bit different from the rest of the album. One is the relative mix of the guitars to the drums, making them seem distant in the background. The other thing is the relative obscurity of the lyrics. It is difficult to wholly understand every word sung by the Wiggin sisters in this song, whereas on the other tracks one can manage to generally follow along.

So how does “Take two” come across as the idea of an outside voice? Well, firstly, he is an outside voice, and the only time he is heard on the album. Otherwise, it is exclusively the Wiggin sisters making sounds. More interestingly, this is the perfect track to include the recording engineer saying, 'OK, this is our second attempt, because the first one completely failed.” Betty, in numerous lines, comes in early with her vocals, however, true to the album's overall sound, they manage to stay somewhat together to finish in a dazzling recapitulation of the song's intro, played even better!

Thus, most of the failures in this song actually come from the meta-voice. It is as if Bob Olive gave up on this song with poor mixing and no attention to getting cleaner vocals. He might have wanted to go home. But The Shaggs stuck it through. They tried it again to produce an ode to the ultimate outside voice and omniscient presence: their “Savior.”

“Take two” at the beginning of this song imbues it with poignancy. When the world has quit on you, you continue nonetheless. In fact, you sing to it, and let it know that it's going to be OK. The last six lines of the album are as innocent as anything that appears on Philosophy of the World:

Why do the people go on killing?

Why do they feel sad and blue?

Don't they know we have a savior?

Just watching over me and you.

Don't

they know we have a savior?

All

we have to do is believe and pray.

In a film where the proportion of establishing shots to the total length of the film is substantial, the viewer gets an unusually long amount of time to reflect on the setting (and it's San Francisco, just in case the viewer forgot over and over again), and to listen to the music that accompanies those shots. The beginning of the main theme for The Room is nothing short of a microcosm for the whole movie. Specifically, the first two larger phrases (heard in The Room Example 4) form an expectation that is never met. The melody starts out innocently enough with a MIDI piano playing the melody (accompanied by MIDI orchestra), maintaining a kind of intimacy (piano soloist vs. orchestra collective). There is enough rhythmic variety at this part of the melody to propel an early cadence in minor, which is quick to come and somewhat surprising, given the theme's quick move to major harmonies. The second part of the first phrase then rises melodically, even extending the 4/4 measure into a 6/4 measure to be able to include the inventive last three notes (which are not needed functionally). Then enter the long suspended cymbal roll to usher in the next phrase. Here, the mixing of the MIDI samples is very odd. Because it seems like the foreground melody should be the entrance of MIDI brass, but what one perceives is 'CHORD!!!' tapered off by an ascending arpeggiation by a MIDI clarinet. Then: 'CHORD!!!' tapered off by an ascending arpeggiation by a MIDI clarinet sequenced down a diatonic step. Then again: 'CHORD!!!' and again the diatonic sequence descends but the clarinet gesture is maintained (diatonically verbatim). Then the V chord and...nothing. No more clarinet. No more anything, in fact, unless you count the return of the 'epic' suspended cymbal roll.

The Room Example 4:

Indeed, it is the score for this film that acts as an outside voice. In most art, an outside voice generally appears to either clear up exposition, play a role in changing the plot (deus ex machina), or act as a cohesive element, providing the transcendental that all fragmented elements in the work can connect to. However, in The Room, the music can distract the viewer, it often has an odd effect. Instead of acting as a mood setter, or an element one can trust to heighten the action, or shedding psychological insight on a character's motivation, the music becomes another feature of eccentric intensity. It is like hearing through the ears of a mentally challenged god. A lot of the times, the viewer is left feeling confusion. Here are a few scenes in which the music plays an awkward role:

- In the flower shop scene (talked about in more detail in “Surprise” and seen in Room Example 3), the music is eerie. As Johnny enters the store, the music grows from an oboe melody in minor to sustained unison strings playing long tones in minor while a piano quietly arpeggiates the chords in a triple meter. It is portentous music, signifying that something ominous awaits, yet, nothing happens. It is a completely mundane scene during which the viewer can feel oddly suspicious since there is almost a surreal effect from the music (and of course, the timing of the dialogue). The music builds an expectation that is never fulfilled.

- The build to the second reprise and first full recapitulation of the main theme is put in a very odd scene in the movie (The Room Example 5).

The Room Example 5:

The scene in question is the one in which Johnny returns home to Lisa with flowers and lets her know about not receiving the promotion at work. She subsequently convinces him to drink a scotch/vodka mixture with her (or “Skotchka” as it is affectionately known at screenings of the film) and seduces him. At first a clarinet and minimal orchestral accompaniment is heard incredibly low in the mix, which builds with filtered noise drones and a slow, high chromatic string melody. This leads into a reprise of the main theme played by a flute and then clarinet in a slower tempo. It's playful, almost wistful, definitely the theme's epic nature is subdued to a fragile one. As they continue drinking, the theme comes back in its original orchestration. This creates a feeling of significance. When the main theme (especially if it is grandiose) of a film returns dramatically, the audience can expect some kind of significance to the scene. This is all fine and good. The weird feeling comes retrospectively when the viewer realizes there was nothing significant about that entire scene. The promotion sub-plot only gets mentioned once again by Lisa to her mom, and the whole reason why Lisa got Johnny drunk was to fabricate a story about how he hit her. Even though this is mentioned, it does not seem to have any actual bearing on anything. Neither Claudette (Lisa's mother) nor Michelle (Lisa's friend who has sex in Johnny's apartment) ever confront Johnny about it, or seem to have a differing opinion of him as a result. The scene retrospectively becomes an odd prelude to yet another gratuitous sex scene.

- The music that enters when Mark accidentally pushes Mike (Michelle's boyfriend) into the garbage cans after he recounts his underwear “tragedy” to Johnny in the alley (described in more detail in “Repetition” seen in The Room Example 1) produces the same sensation as the entire drinking scene, however, that feeling is not retrospective. Immediately the viewer feels the absurdity of the situation. The music is intense as if Mike might have to go to the hospital (and indeed, he is asked if he needs to see a doctor by a dubbed recording although it does not line up with any of the characters). The high foreboding strings again paint a doom-like feeling that Mike might be seriously injured, or, that Mark's aggression was completely unwarranted. It is this bizarre expansion of an insignificant detail that confuses the viewer. For instance, the same effect is created on a bit of a smaller scale when Mark enters in a tuxedo for the wedding picture day(?), and suddenly it cuts to Mark as the camera dollies in for a close up as a chord with harmonic tension is arpeggiated by a harp and celeste, basically to show Mark's newly clean-shaven face to which Johnny, Denny and Peter react very enthusiastically (seen in The Room Example 6):

The Room Example 6:

This poem is a quintessential example of melodrama. It is saturated with despair to appeal to the reader's emotions, and to have the reader sympathize with the speaker's plight. The language is over-the-top (to say the least) and punctuated by silly onomatopoeia (the sounds of nature around the speaker) which remind the reader of the speaker's setting: he is at some body of water about to drown himself.

There is, however, a subtle reciprocity between the speaker and his natural surroundings. If one drowns, one is filled with water and it ultimately asphyxiates the person drowning: a rush of nature completely filling one's body. In lines 18-22, the speaker is describing the sensations of feeling empty. His thoughts are gone (even though he continues the poem for quite some time) and his love is disappearing (even though he becomes even more impassioned in lines 31-46) from his body and into nature. It is as if his action completes the exchange of ugliness between his inner spirit (leaving) and the ugliness of his surroundings he is describing (entering). It is only fitting that the suicide of the speaker fulfills a balance of this sort, as if nothing ever happened and it all cancelled out. This is because it is doubtful that a reader can come to feel any kind of shared despair for him.

Although it is initially difficult to take the lyrics on this album seriously, there is also an aspect of despair that comes through. It is hard to at least deny the sincerity of these lyrics. Picture three teenage girls forced to rehearse and write songs by their father who is convinced they will be famous. Top that with growing up in an isolated town in New Hampshire, and being restricted in going out and socializing with contemporaries (let alone dating or kissing any boys). So, how does one begin to write lyrics about romantic heart break given that situation? Well, the answer seems clear. There is a kind of pain communicated on this album, and it might be a naïve isolated teenage girl's pain, but it is undoubtedly honest.

If we were to categorize the album's songs based solely on an overall feeling the lyrics create, I might propose the following:

Bleakness/Despair:

Philosophy of the World

I'm So Happy When You're Near

Things I Wonder

Sweet Thing

What Should I Do?

Fear:

That Little Sports Car

My Pal Foot-Foot

Why Do I Feel?

Hope/Re-Assurance:

Who Are Parents?

My Companion

It's Halloween

We Have a Savior

The last song (“We Have a Savior”) might even be considered in the first category since it paints such a pessimistic view of mankind's predilection for destruction. I only categorize these songs to point out how much of the songs deal with dark themes (at least two thirds of the album).

And despair is not just present in some of the lyrics; here are a few examples in which despair is expressed musically as well:

- The opening track (title track) paints a dichotomy if a listener is taking the lyrics seriously. The “hook” of the song is incredibly upbeat followed by re-affirming drum fills (“You can never please anybody in this world!”); yet, this is a completely defeatist outlook.

- The amount of vocalized time spent in the penultimate song on the title lyrics, “What should I do?” creates an odd proportioning. Since that question ends most stanzas of verse, and The Shaggs dwell a bit instrumentally (mostly lost or wandering) after each one, there is a possibility that they are reflecting, but also ultimately waiting for an answer, though that answer never comes and so they are perpetually stuck asking the same question and always remaining in limbo and in despair.

- Perhaps one of the most poignant moments on the album comes at the end of the second track, “That Little Sports Car,” when they sing: “I turned around and headed for home/I learned my lesson never to roam/I learned my lesson never to roam/Never to roam/Never to roam/Never to roam/Never to roam.” This is heard in Shaggs Example 8:

Shaggs Example 8:

One can clearly interpret this not just in the context of the song (the sports car is too fast for them to catch), but in the greater context of their teenage lives. They were brought up sheltered within a sheltered town, taught “never to roam.” The song opens with a chromatically descending figure in the guitar that proceeds to a VI-VII-I chord progression to (semi-)establish the key. At two points in the song prior to the lyrics mentioned above, the guitar has a quicker figure that this time rises in pitch contour and is (mostly rhythmically) doubled by the ride cymbal:

Shaggs Example 9:

The third time it is presented even higher followed directly by an instrumental rendition of the main verse melody:

Shaggs Example 10:

Then the “roaming” lyrics enter. After they repeat “learning their lesson,” they take a turn each singing in an ascending melody that progressively gets higher with each subsequent iteration: “Never to roam,” as if this was the bell of the heavy burden of truth constantly tolling in their minds; then they sing it together higher, and then they sing it together even higher but this time extend the word roam durationally for a relatively long time. In addition to this, the melodies thus far have been strictly within the off-tuning of the guitar (which definitely approximates a key), but the pitches sung here are completely outside of, not only the key, but of the entire tuning system they have employed. The dissonance is striking even amidst all of the dissonance they create by not being able to tune traditionally. This entire rising melody matches the futility of the rising guitar gestures, which again are reiterated one final time (but back to the original pitch level as in Shaggs Example 9), showing the limit of roaming in pitch space too.

The Room's portrayal of Johnny's plight of despair is extreme. His character is set up to be perfect, without flaw and well-loved by everyone around him. He doesn't even drink! How can he be driven to such extreme despair if he is without flaw? Surely his perfection should enable him to overcome even the most intense heartbreak situation. Yet, it his decision to kill himself at the end of the film that validates his perfection. Johnny can only think of others, in fact, his life is defined by the others around him. Who would he be if it weren't strictly for his compassionate acts (the dress and flowers for Lisa, paying for Denny's apartment and tuition, saving Denny from the drug dealer, letting Michelle and Mike have sex in his apartment, giving advice to Mark,etc.)? That is why the scene in which Johnny confronts Lisa and denies that he ever hit her is so crucial in showing his utter inability to live without his true love.

The Room Example 7:

He tells her “You are part of my life, you are everything. I could not go on without you Lisa” shortly before the famous delivery of “You are tearing me apart Lisa!!” This is the first scene we truly get a glimpse of how emotional and quickly filled with despair Johnny can become (more on that in a bit). While Johnny personifies true goodness, Lisa is the personification of evil, though not necessarily true evil (because she shows moments of humanity, for instance when she tenderly describes Johnny's compassion to her mother and the viewer finally learns who Denny is). If one reads the scene from The Room Example 7 dialectically, one can even say that evil is a necessary component of Johnny's goodness. His perfection only exists because his true love's evil nature is in his very soul. This is what allows Johnny's immaculate character to destroy the room in which most scenes of the film take place, and doubtless, where the title of the film comes from.

The Room Example 8:

The symbolism of destroying the sanctuary that Johnny has created in this room ties in with his own suicide. The room has come to be where Johnny's innermost emotions, thoughts and actions take place, a sort of soul for Johnny. Johnny needs that aspect of Lisa that is in him in order to destroy his very own perfection, and indeed, soul. Her betrayal, her absence crumbles the sanctuary, and of course, Johnny's life.

Time is often a necessary agent in the spread of personal despair. One needs time to brood, to let emotions build and intensify, and to reflect before coming to the conclusion that all is hopeless. In the case of Johnny, this happens rather quickly. At best, the viewer has an ambiguous sense of how much time has elapsed in the film in order for Johnny to come to the final conclusion that he has no hope of going on without Lisa. The failure in this element is that time is not felt as a build up, or method of allowing the viewer to sympathize with Johnny's despair. Instead, Johnny's despair (and indeed, the other characters' despair) distorts time.

Throughout the film, the viewer is challenged to try to follow how much time has elapsed in the story. This is obfuscated by the copious amounts of establishing shots which can all of a sudden switch to night time shots (à la Ed Wood) or daytime shots seemingly at random. I'd like to point out three examples which pair despair with the distortion of time:

-The two scenes which precede the scene in which Johnny, Denny, Mark and Peter are in their tuxedos (The Room Example 9) show to some extent the emotional turmoil that Lisa and Mark are going through.

The Room Example 9:

Lisa retorts that she has “plenty of time” when Denny points out that “the wedding is only a month away.” Here we can see Lisa's fervent denial that anything is wrong, yet here we see that internally she does want to somehow tell Johnny that she does not love him anymore.

The next scene takes place immediately after with Mark and Peter on the roof (The Room Example 10). Peter guesses what's depressing Mark(his affair with Lisa), and Mark threatens to throw Peter off the roof only to apologize a few seconds later and then continue the discussion as if nothing has happened (observe the jump cut at 0:34 in The Room Example 10 and how this also completely throws off the viewer's sense of time, because it is only a jump cut of one or two seconds, the time it would take Mark to first walk over to the table and then violently kick it. However, within this time span, the action all of a sudden returns to the violence we saw just before when Mark was forcibly holding Peter over the edge of the building).

The Room Example 10:

After they leave the roof, there is a quick establishing shot to show some indeterminate passage of time. Then the scene opens up in the room with Johnny in a tuxedo on the phone. Denny, Peter, and then Mark all enter with their tuxedos, supposedly because they are taking wedding pictures. Aren't wedding pictures taken the day of the wedding? Has a month actually passed? The point of this tuxedo scene is one of the most enigmatic of all eccentricities in this film. The scene might also take place the following day, or a couple of days later. Either way, it is not clear.

-One successful scene in which the viewer can potentially connect with Johnny emotionally and viscerally happens when he overhears Lisa telling her mother that she does not love Johnny anymore, and that she has slept with someone else (although it is a bit ridiculous that Johnny just happens to be home from work (presumably) on the staircase less than fifteen feet away from Lisa and Claudette and that they don't notice). The scene offers his heart-broken (but determined) reaction and decision to tape record all subsequent phone conversations. The scene (The Room Example 11) lasts for one minute and twenty-five seconds of mostly showing Johnny assembling the recording device to the phone (and magically taking out a clean cassette tape from his pocket).

The Room Example 11:

This is an unusually long amount of time to show something that is so tangential to the plot which can easily be shown within a few seconds. For the viewer, this serves as a detailed step-by-step guide on how to hook up a recording device to record all of your phone conversations! One would expect that this somehow has some kind of significance. Indeed, near the end of the film after the party when Johnny locks himself in the bathroom and hears Lisa speaking to someone on the phone he implores her to reveal the identity of whom she was speaking to (when it very obviously is Mark). When she refuses to answer, Johnny goes downstairs to get the cassette tape. The failure in the believability of this scene is so pronounced (partially due to the abnormal amount of time spent showing how he was to record the phone conversation earlier in the movie) because he shows the tape, which is completely rewound, and as soon as he puts it into a tape player, it immediately starts at the conversation Lisa just had. How much time has elapsed between the scene in which Johnny starts recording to the present scene? A week? A month? How long can a tape record for? It is amusing to spend that much time on a scene only to have it wind up failing (plot-wise) upon its return. After Johnny plays the recording, he says “I gave you seven years of my life!” Lisa corroborates this moments later. However, in the beginning of the movie it is explicitly stated that Johnny and Lisa have known each other for five years. The time distortion seems to appear on all levels, no matter how mundane the detail. Lisa leaves shortly after and Johnny goes into his fit of rage and despair. He is haunted as he remembers all of the times he has shared with Lisa, but apparently only from the last few days(?):

The Room Example 12:

Johnny's despair is difficult to accept in part because the viewer rarely has a sense of how much time is actually elapsing.